Introduction

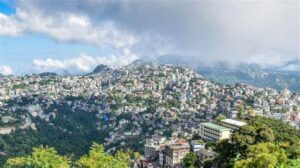

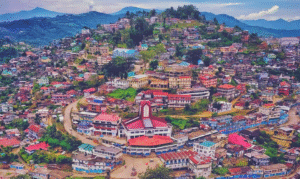

India is a land of diverse cultures, and its festivals reflect the deep connection people have with nature, agriculture, and ancestry. Among the many indigenous festivals celebrated in Northeast India, Mim Kut stands out as a poignant tribute to ancestors. Celebrated predominantly by the Zo or Mizo community of Mizoram, Mim Kut is a harvest festival observed after the gathering of maize. It carries both festive and mournful tones—combining the joy of harvest with remembrance of the dead. This academic and educational blog delves deep into the origins, rituals, cultural importance, and evolving relevance of Mim Kut in contemporary Mizo society.

Historical and Cultural Background

Mim Kut is one of the oldest festivals of the Mizo people, predating even the arrival of Christianity in Mizoram in the late 19th century. It is believed to have originated from a time when the Mizos lived in the Chindwin Valley (now in Myanmar), before migrating into present-day Mizoram. The term “Mim” refers to maize (corn) and “Kut” means festival—so it literally translates to “maize festival.”

What distinguishes Mim Kut from other agrarian festivals is its funereal significance. Unlike other Kuts like Chapchar Kut or Pawl Kut, which celebrate life and prosperity, Mim Kut serves as a memorial ritual. It is observed to honor deceased ancestors, particularly those who have passed away in the previous year. This connection with ancestral spirits is reflective of the Mizo people’s deep-seated animistic and spiritual traditions, which were prevalent before the widespread adoption of Christianity.

Agricultural Context: The Harvest of Maize

Maize is not a staple crop in Mizoram today, but it historically held importance in the Mizo agricultural cycle. Mim Kut coincides with the end of the maize harvest season, typically in August or September. This timing is not arbitrary—agriculture in tribal societies is intrinsically tied to the rhythms of nature, and festivals serve as calendar markers for sowing, harvesting, and resting periods.

The post-harvest period is a time of abundance, when the granaries are full and people can afford to turn their attention to religious and social observances. Mim Kut, therefore, represents a pause in the agricultural calendar—a moment to reflect, remember, and reconnect with the past.

Ritual Practices and Observances

Traditional Mim Kut observances span several days and involve rituals, feasts, singing, and drinking, but the central theme remains remembrance of the dead. Key ritual elements include:

1. Offering of First Fruits

Mizos believe in appeasing ancestral spirits by offering them the first fruits of the maize harvest. These offerings are usually placed on memorial platforms or graves and include maize, rice beer, vegetables, and sometimes meat. The belief is that the spirits of the departed return during Mim Kut to partake in the offerings.

2. Wailing and Lamenting

Unlike other celebratory festivals, Mim Kut includes ritual lamenting. Women in particular would mourn loudly, crying for their lost relatives. This is not seen as a display of weakness, but rather as a necessary cathartic act—grief made public, sacred, and shared.

3. Feasting and Rice Beer (Zu)

Despite its mournful tone, Mim Kut is also a time of community gathering. Traditional feasts are prepared and Zu, a local rice beer, is consumed in moderation. The sharing of food and drink serves to reinforce community bonds, affirm life, and mark the cyclical nature of death and rebirth.

4. Cultural Performances

Traditional folk songs (Hlado) and dances are performed during Mim Kut. Some songs narrate tales of warriors and ancestral lore, while others express melancholy and longing for the departed. These performances serve as oral archives, preserving Mizo culture across generations.

Significance of Ancestor Worship in Mizo Culture

Mim Kut is deeply rooted in the pre-Christian spiritual worldview of the Mizos, which included elements of animism and ancestor worship. The belief was that the dead resided in a spirit world and could exert influence on the living—either offering protection or causing misfortune if neglected.

The festival functioned as a ritual of continuity, keeping the dead present within the community’s collective memory. It also emphasized the interconnectedness of life and death, a theme prevalent in indigenous cultures around the world.

Even after the advent of Christianity, which largely discouraged such practices, the cultural significance of Mim Kut has survived—albeit in modified, symbolic forms.

Transformation Over Time

The arrival of Christian missionaries in the late 19th century dramatically altered the religious landscape of Mizoram. Many traditional beliefs, including those associated with Mim Kut, were labeled as “pagan” and discouraged. As a result, public mourning rituals, ancestor worship, and offerings to spirits declined in favor of Christian memorial services.

However, Mim Kut did not disappear. Instead, it adapted to the changing socio-religious context. Today, the festival is often celebrated in a cultural rather than religious capacity, with an emphasis on heritage, folklore, and traditional identity. Schools, cultural organizations, and village councils organize events that include folk dances, storytelling, and exhibitions.

This transformation demonstrates the resilience of indigenous identity in the face of modernization and religious change. Mim Kut has become a marker of ethnic pride, particularly for younger generations who are keen to reclaim their cultural roots.

Mim Kut in the Contemporary Context

In today’s Mizoram, Mim Kut plays a multifaceted role:

1. Cultural Preservation

Mim Kut has emerged as a key platform for reviving traditional arts, including weaving, woodcraft, music, and dance. It offers an opportunity for elders to pass down knowledge and for younger generations to reconnect with their heritage.

2. Community Bonding

Even in urban settings, Mim Kut celebrations help foster unity among Mizo communities. It provides a context for intergenerational dialogue, where families remember ancestors and share cultural stories.

3. Tourism and Soft Diplomacy

Mim Kut is gaining recognition beyond Mizoram as part of the region’s cultural tourism initiatives. Government efforts to promote Northeast India’s diversity include festivals like Mim Kut, which attract both domestic and international visitors. However, care must be taken to ensure that cultural commodification does not dilute traditional meaning.

4. Ritual Adaptation

In Christian households, Mim Kut has been harmonized with church memorial services. Instead of food offerings, families might organize prayer meetings or gatherings to remember the departed. This blending of traditional and modern forms reflects the dynamic nature of cultural practices.

Challenges and Cultural Sensitivities

Despite its cultural richness, Mim Kut faces certain challenges:

- Urbanization: With increasing migration to cities, traditional agricultural cycles are no longer central to daily life. As a result, the agro-spiritual connection that underpins Mim Kut is weakening.

- Religious Tensions: Some conservative Christian groups still view Mim Kut as incompatible with their faith. This has created debates within the community about the “right” way to celebrate it.

- Loss of Oral Traditions: With modernization, oral storytelling and folk songs are in decline. Efforts are needed to document and teach these traditions in schools and cultural programs.

Nevertheless, these challenges are not insurmountable. They reflect the evolving nature of culture—always adapting, negotiating, and surviving.

Comparative Perspective: Mim Kut and Other Ancestor Festivals

Mim Kut can be contextualized within a global framework of ancestor veneration festivals:

- In China, the Qingming Festival involves cleaning ancestral graves and making offerings.

- In Mexico, Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) is a colorful celebration of departed souls.

- In parts of Africa, Libation rituals are common to honor ancestors.

These parallels show that honoring the dead through seasonal festivals is a universal human practice, driven by the desire to maintain continuity across generations.

Conclusion

Mim Kut is more than a harvest festival—it is a ritual of remembrance, identity, and continuity. Rooted in Mizo agricultural life and spiritual beliefs, it bridges the world of the living and the dead. While the traditional forms of the festival may have changed over time, its emotional and cultural core endures.

In an era of rapid change, festivals like Mim Kut offer a grounding sense of who we are and where we come from. They remind us that death is not just an end, but also a part of the cycle of life—to be mourned, remembered, and celebrated.