Introduction

Chapchar Kut is the most vibrant and widely celebrated festival of the Mizo people in the northeastern state of Mizoram, India. Observed in early March, this spring festival marks the completion of jhum (slash-and-burn) cultivation’s initial stage—specifically, the clearing of the jungle. The festival not only signifies the end of winter but also welcomes a period of rest and rejoicing before the strenuous task of planting begins.

More than a seasonal marker, Chapchar Kut is a cultural cornerstone, blending traditional Mizo heritage, folk performances, community bonding, and indigenous cuisine. In recent decades, the festival has gained prominence beyond Mizoram as a showcase of the state’s identity and customs.

Historical Background of Chapchar Kut

The roots of Chapchar Kut trace back centuries, possibly to the 15th century during the era of the Mizo chieftains in the Lushai Hills. Historically, Mizo society practiced jhum cultivation, which required extensive clearing of forested areas. After the trees were cut and before they were burned—a period that could last a few weeks—the farmers would rest.

This interval gave rise to Chapchar Kut, originally a festival of relaxation and gratitude among cultivators. While the modern celebration has evolved, it still preserves the essence of rest, togetherness, and cultural renewal.

According to oral history, the first Chapchar Kut was celebrated in a village called Suaipui. Over time, it became institutionalized in other Mizo settlements. It was briefly discontinued during the spread of Christianity in Mizoram in the early 20th century due to its association with alcohol and pre-Christian rituals. However, in 1973, the festival was revived by the Mizo Zirlai Pawl (Mizo Students’ Union), and has since been celebrated as a cultural, secular event that reinforces Mizo identity.

Etymology and Timing

The term Chapchar Kut is derived from two Mizo words:

- Chapchar – referring to the season when trees and bamboo are felled but not yet burned.

- Kut – meaning festival.

This places the celebration firmly within the agricultural calendar. Typically observed in March, it signals the beginning of spring and the end of the labor-intensive winter clearing season.

Rituals and Celebrations

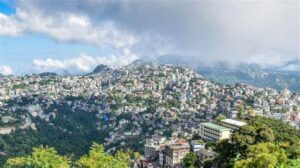

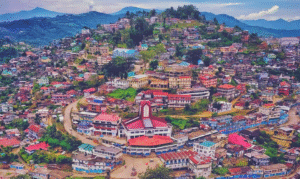

Chapchar Kut festivities typically span a few days, involving both rural and urban communities. In Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram, the celebrations are particularly elaborate, with state-level functions and cultural performances held at venues like the Assam Rifles Ground or Lammual.

Key Elements of Celebration:

- Traditional Attire and Costumes

Participants dress in colorful traditional Mizo attire. Women wear the puan (handwoven wraparound cloth), while men don traditional headgear, vests, and sword belts. This visual celebration of Mizo heritage reinforces cultural continuity and pride. - Cultural Dances and Music

The highlight of Chapchar Kut is the performance of the Cheraw Dance—Mizoram’s iconic bamboo dance. Women perform graceful steps between moving bamboo poles while men rhythmically clap them. Other traditional dances like Khuallam, Chheihlam, and Tlanglam are also performed, each telling stories of valor, love, or community. - Community Feasting

Food plays a central role. Traditional Mizo dishes like bai (vegetable stew), arsa buhchiar (rice cooked with chicken), and local rice beer (zu) are served during communal feasts. Today, the consumption of alcohol is often replaced with symbolic offerings in keeping with modern social norms. - Ethnic Parades and Pageantry

Cultural processions showcasing various tribes and clans of Mizoram add vibrancy to the event. Pageants, art exhibitions, and traditional sports such as archery and wrestling also feature prominently. - Religious and Social Programs

While Chapchar Kut is secular today, some religious organizations also participate by holding prayer services for peace, prosperity, and a good agricultural season ahead.

Socio-Cultural Significance

Chapchar Kut is more than a seasonal festivity—it is a statement of identity, resilience, and cultural preservation for the Mizo people.

1. Preservation of Indigenous Practices

The festival is a living archive of Mizo traditions. By involving younger generations in folk dance, costume, and cuisine, it ensures that indigenous knowledge systems and cultural expressions are passed down.

2. Promoting Unity and Community Spirit

Chapchar Kut brings together people from all walks of life, transcending age, religion, and profession. It reinforces social cohesion and reminds the community of its shared agricultural roots.

3. Revival of Folk Arts and Crafts

Local artisans, weavers, and musicians find a renewed platform during this festival. The demand for traditional attire, ornaments, and instruments surges, thereby supporting local economies and craftsmanship.

Chapchar Kut in Contemporary Times

With globalization and urban migration impacting rural traditions, festivals like Chapchar Kut play a vital role in cultural sustainability. The Mizoram government has taken steps to promote it as a tourism and cultural event. Educational institutions also organize themed programs to educate students about its significance.

In recent years, Chapchar Kut has also served as a stage for environmental awareness, with themes emphasizing sustainable agriculture, forest conservation, and cultural harmony.

Social media and digital platforms have further amplified its reach, helping Mizo diaspora communities across the globe reconnect with their heritage.

Challenges and Future Prospects

Despite its celebratory appeal, Chapchar Kut faces certain challenges:

- Commercialization: The shift from community-driven to state-sponsored events risks commodifying the festival.

- Urban Disconnect: Younger generations in urban settings may engage more with the aesthetic aspects than the cultural or agricultural relevance of the festival.

- Environmental Concerns: Given its link to jhum cultivation, which is under scrutiny for environmental impact, there’s a need to reinterpret the festival’s meaning in an ecologically sensitive manner.

However, these challenges also open up opportunities for dialogue—between tradition and modernity, between environmental consciousness and cultural pride.

Conclusion

Chapchar Kut is not just a Mizo festival—it is a chronicle of resilience, rhythm, and renewal. As the hills of Mizoram echo with drumbeats and bamboo claps, this spring celebration reaffirms the Mizo people’s deep-rooted connection to nature, community, and cultural identity. In an era of rapid change, festivals like Chapchar Kut are vital for maintaining the delicate balance between progress and tradition.

Its continued observance is not just an act of celebration—but a living testament to the spirit of Mizoram.