Introduction

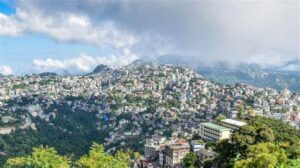

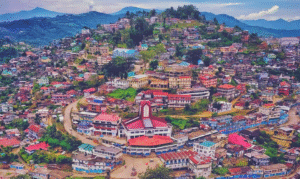

Jhum cultivation—also known as shifting cultivation, slash-and-burn agriculture, or swidden farming—is an ancient agricultural method still practiced by many indigenous communities in Northeast India, particularly in states like Nagaland, Mizoram, Manipur, Tripura, Meghalaya, and Arunachal Pradesh. While the technique has often been viewed critically through modern agricultural lenses, it is deeply rooted in traditional customs, spiritual beliefs, and ecological understandings of the tribal communities who practice it.

This blog explores Jhum cultivation not just as an agricultural system but as a complex cultural and ritualistic process, encompassing community participation, seasonal rituals, environmental wisdom, and indigenous identity.

What is Jhum Cultivation?

Jhum cultivation is a form of agriculture where land is cleared by cutting down forest vegetation, which is then dried and burned before the first rains. Seeds are sown directly into the ashes, and after a few years of cultivation, the land is left fallow to regenerate while farmers move to a new patch of forest.

This method is:

- Labor-intensive

- Dependent on natural cycles

- Managed collectively

- Intertwined with ecological understanding and spiritual reverence for nature

Contrary to perceptions of it being environmentally destructive, traditional Jhum cultivation often follows sustainable cycles—provided the fallow period is long enough for the land to regenerate.

Cultural Importance of Jhum Cultivation

For many tribal groups, agriculture is not just about food production—it is a way of life. Jhum cultivation is woven into their myths, folklore, songs, and community life. The land is not viewed as a commodity but as a living entity that requires respect, gratitude, and balance.

Key cultural elements include:

- Collective decision-making by village elders

- Ceremonies and festivals tied to different phases of cultivation

- Gender-specific roles in farming and rituals

- Deep ecological knowledge passed through oral traditions

Thus, Jhum becomes both an economic activity and a socio-cultural institution.

Annual Cycle and Ritual Phases

Jhum cultivation follows a highly ritualized annual calendar. Although the specific names and customs vary across tribes, the broader phases are remarkably consistent:

1. Selection of Land (December–January)

The first stage is the selection of the forested plot to be cultivated. This decision is often taken by a council of elders or experienced farmers who assess:

- Soil fertility

- Proximity to water sources

- Previous usage history

Rituals:

- Offerings to forest spirits or deities are made before cutting begins.

- Some communities observe fasting or abstain from certain foods during this period as a sign of respect to nature.

2. Clearing and Slashing (January–February)

Once the land is selected, the vegetation is cut using tools like daos (machetes). This phase demands collective labor.

Rituals:

- Specific trees may not be felled due to sacred associations.

- In many tribes, the first tree cut is symbolically offered to the deities.

- Songs are sung while cutting to invoke blessings and share communal energy.

3. Drying and Burning (March)

The cut vegetation is left to dry under the sun for several weeks. After drying, it is burned before the pre-monsoon rains.

Rituals:

- The burning is accompanied by chants to purify the land and ward off evil spirits.

- Some tribes conduct rituals to seek permission from the land spirit before lighting the fire.

This phase is crucial, as the ash enriches the soil, creating a fertile bed for sowing.

4. Sowing of Seeds (April–May)

With the onset of rain, the sowing begins. Seeds of multiple crops—millets, maize, rice, yams, and beans—are sown together using pointed wooden sticks instead of ploughs.

Rituals:

- Seed-sowing is often preceded by a community feast and dance.

- Seeds are sometimes ritually blessed by the village priest (or priestess).

- Women play a central role in selecting, preserving, and sowing seeds, reinforcing their role as guardians of biodiversity.

5. Weeding and Maintenance (June–August)

During the growing season, fields are weeded manually. The community helps each other in turns, maintaining strong social cohesion.

Rituals:

- There are songs and chants sung during weeding to lighten the labor and praise the fertility goddess.

- Restrictions on behavior may apply, such as abstinence from alcohol or specific activities during key growth phases to maintain the sanctity of the crops.

6. Harvesting (September–October)

Crops are harvested manually. This is one of the most joyous times of the year.

Rituals:

- The first sheaves are often offered to the gods or ancestral spirits before general consumption.

- Harvest festivals like Kut (Mizo), Sekrenyi (Angami), and Wangala (Garo) are celebrated with dancing, singing, and communal feasts.

- Elders bless the harvest and distribute it among families, ensuring no one is left hungry.

7. Fallow and Regeneration (2–10 years)

After 1–2 years of cultivation, the land is left fallow for a natural regeneration period. During this time, the forest is allowed to grow back, replenishing nutrients.

Beliefs and Customs:

- The land is considered “resting” and is not disturbed.

- Sacred groves may be left untouched to ensure ecological balance.

- Young children are taught not to venture into these areas, reinforcing early environmental education.

Intergenerational Knowledge and Ecological Understanding

One of the most fascinating aspects of Jhum cultivation is how knowledge is passed from one generation to the next. There is no written manual—everything is learned through observation, participation, and storytelling.

Farmers can predict:

- Weather patterns

- Soil fertility based on leaf coloration

- Pest control through intercropping and plant biodiversity

This embedded knowledge is a form of indigenous science that coexists with ritual and spirituality.

Variations Across Tribes

Different tribal communities have their own unique interpretations and practices of Jhum. A few examples:

- Mizo Tribe (Mizoram): Celebrates the festival of Chapchar Kut, marking the completion of the slashing phase.

- Ao Tribe (Nagaland): Observes Moatsu Mong festival after the sowing period, symbolizing rest and community bonding.

- Garo Tribe (Meghalaya): Practices shifting cultivation in hilly terrain and incorporates animistic rituals in every agricultural phase.

- Adi Tribe (Arunachal Pradesh): Practices Jhum with altars dedicated to nature gods, with women playing a central ritual role in sowing and harvest.

Each tribe adapts Jhum to its topography, rainfall, and sociocultural context, making it a diverse but interconnected system.

Socio-Economic and Gender Dimensions

Jhum cultivation is more than farming—it is a socio-economic structure:

- Labor is shared and reciprocated across families.

- Land ownership is often communal or clan-based.

- Women’s roles in seed selection, ritual practices, and harvest management are vital.

This communal and inclusive model builds a sense of equity and environmental stewardship.

Challenges and Modern Debates

In recent decades, Jhum cultivation has come under scrutiny. Government policies have labeled it as unproductive, environmentally damaging, and a cause of deforestation. Farmers are often encouraged to switch to terrace farming or settled agriculture.

Key Issues Raised:

- Decreased fallow periods due to population pressure

- Erosion of ritual knowledge as younger generations migrate to cities

- Loss of biodiversity with monocropping initiatives

- Conversion of Jhum land into commercial plantations

However, scholars and ecologists argue that:

- The ecological damage occurs only when fallow periods are shortened unnaturally.

- Jhum systems are often more resilient to climate change than monocultures.

- Cultural erosion is a greater threat than environmental degradation.

Revival and Sustainable Adaptations

Some efforts are being made to revitalize Jhum cultivation by blending traditional wisdom with scientific support:

- Agroforestry models that extend Jhum practices while maintaining biodiversity.

- Community seed banks to preserve indigenous seed varieties.

- Ethnobotanical documentation to archive rituals and farming knowledge.

- Eco-cultural tourism that supports indigenous livelihoods while preserving traditions.

Moreover, policies that acknowledge indigenous rights and provide land tenure security are vital to the preservation of Jhum’s cultural-ecological balance.

Conclusion

Jhum cultivation is not merely a farming practice—it is a living tradition that integrates food security, community cohesion, ecological wisdom, and spiritual belief. For the tribes of Northeast India, the cycle of Jhum is a cycle of life itself: a balance of labor and leisure, discipline and festivity, nature and culture.

As the world re-evaluates sustainability and the value of indigenous knowledge systems, Jhum cultivation deserves recognition—not as a relic of the past but as a resilient, community-centered, and environmentally conscious practice. Preserving the rituals, knowledge, and rights of the communities who practice Jhum is not just about protecting tradition—it’s about nurturing a more sustainable and inclusive future.