Introduction

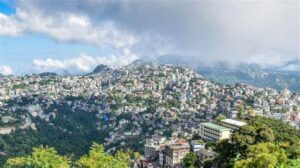

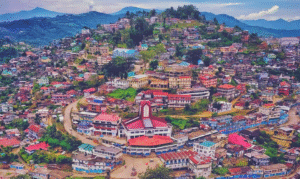

Hidden in the rugged hills of Nagaland, around 20 km west of Kohima, lies Khonoma Village—Asia’s pioneering “Green Village.” A confluence of rich cultural heritage, fierce historical legacy, and path-breaking environmental stewardship, Khonoma represents a compelling case study in community-led sustainability. Over the past few decades, Khonoma has evolved from a traditional hunting settlement to a beacon of conservation, earning recognition as India’s first green village. This blog explores Khonoma through an academic lens, examining its historical roots, cultural evolution, ecological strategies, biodiversity, sustainable governance model, tourism integration, challenges, and broader implications for global environmental management.

1. Historical and Cultural Context

1.1. The Warrior Legacy

Khonoma is an Angami Naga village—home to around 1,943 residents across 424 households—whose history extends over 500 years (en.wikipedia.org). It is renowned for the “Battle of Khonoma” (1830–1880), where its warrior clans fiercely resisted British incursions, inflicting considerable losses before the colonial army established control (incredibleindia.gov.in). This martial tradition shaped a strong sense of identity and self-governance that later underpinned community-led environmental action.

1.2. Animist Traditions and Hunting

For centuries, hunting was central to Angami life—not just as subsistence but as a sacred ritual . Deer, pigs, birds, and wild buffaloes were hunted in ceremonial and seasonal events. The villagers believed that consuming hunted animals brought spiritual fortune, and trophies were displayed as symbols of prestige.

2. The Conservation Turning Point

2.1. Ecological Alarm

A tipping point in conservation consciousness came around 1993, when villagers killed approximately 300 endangered Blyth’s tragopans in a single week during a hunting contest (india.com). This event shook the community, stirring concern among elders and conservation-minded individuals who feared for wildlife’s survival.

2.2. Sanctuary Declaration

After five years of deliberation and external consultation with forestry officers, environmentalists, and NGOs, the village council declared a 20 km² region as the Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary (KNCTS) in 1998 (india.com). This act not only prohibited hunting and logging but served as a powerful statement of community self-regulation—at a time when only governments typically designated protected areas .

2.3. Expanding Conservation

Subsequently, the ban extended beyond sanctuary bounds to encompass the entire forest area managed by the village—some 125 km² in total . This progressive scaling reflected the depth of community-driven environmental governance.

3. Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration

3.1. Flora and Fauna

Khonoma is nestled within biologically rich ecoregions—ranging from Himalayan subtropical forests to montane and pine ecosystems (theguardian.com, en.wikipedia.org). The sanctuary is a recognized Important Bird Area (IBA) defined by the presence of threatened species like the Blyth’s tragopan, mountain bamboo partridge, and Naga wren-babbler (en.wikipedia.org).

Mammalian residents include clouded leopards, Asiatic black bears, Serows, hoolock gibbons, and sloth bears (en.wikipedia.org). In total, more than 250 plant species (70 of which have medicinal value), 45 orchid species, 11 bamboo species, and 196 bird species have been recorded (incredibleindia.gov.in).

3.2. Wildlife Recovery

Following the hunting ban, key wildlife populations rebounded. For example, tragopan numbers increased dramatically from near extinction to flourishing populations exceeding 1,000 . This rejuvenation showcases the effectiveness of traditional lockdowns on hunting combined with habitat protection.

4. Socio-Economic Transformation

4.1. From Hunters to Wardens and Ecologists

In a role reversal, former hunters were appointed as eco-wardens to patrol and enforce conservation measures, supported by initial funding from the Gerald Durrell Memorial Fund (theguardian.com). This integration of local stakeholders into management roles ensured continued enforcement and ownership of conservation ethics.

4.2. Sustainable Livelihood Diversification

To offset the loss of hunting, Khonoma villagers pivoted to alternative income-generating activities:

- Homestays & Eco-tourism: The first homestay began in 2006; by 2019, 12 homestays hosted around 4,000 tourists annually (theguardian.com).

- Guiding Services: Local youths serve as nature and cultural tour guides.

- Handicrafts: Skilled basketry, weaving (e.g., Khuophi baskets and traditional shawls), carpentry, and stone carving offer marketable cultural goods (unconventionalandvivid.com).

- Organic & Alderson Jhum Agriculture: Hansom terraced rice farming, millet, corn, vegetables, and alder-based shifting cultivation fortified community food security .

- Plant Nurseries: Women-led nurseries (e.g. poinsettias) diversified income (theguardian.com).

Such diversification improved living standards, funded education access, and enabled healthcare provisioning.

4.3. Recognition and Institutional Support

Khonoma has garnered numerous accolades:

- Declared India’s first Green Village in 2005 (en.wikipedia.org).

- Appointed to UNWTO’s Tourism Village Upgrade Program (2022)—a unique recognition in Southeast Asia (morungexpress.com).

- Received India’s National Biodiversity Award (2021) for innovative alder-based jhum cultivation (morungexpress.com).

5. Governance Model & Social Institutions

5.1. Village Council Leadership

Khonoma Village Council—a democratically elected local administrative body—played a central role in decision-making processes like sanctuary creation, bans on resource extraction, and tourism regulations (en.wikipedia.org).

5.2. Khonoma Youth Organisation (KYO)

Youth cohort KYO enforces sanctuary rules, imposes fines for violations, and maintains social norms. Their patrols are supplemented by social stigma as a non-monetary deterrent .

5.3. Community Alliances

Khonoma spearheaded the formation of the Nagaland Community Conserved Areas Forum (NCCAF) in 2014, helping replicate its model across 100+ CCAs in the state (theguardian.com).

6. Eco‑Tourism and Education

6.1. Tourism Development

Khonoma carefully transitioned to responsible tourism: homestays were constructed to reflect local architecture; visitors are encouraged to adopt leave-no-trace etiquette; and guides trained to highlight eco-conscious practices .

6.2. Environmental Awareness

Ongoing cleanliness drives by Khonoma Village Students’ Union (KVSU)—especially during picnics—combat litter, plastic pollution, and alcohol bottle disposal (morungexpress.com). Their motto underscores sustainability: “take nothing but photos, leave nothing but footprints” (morungexpress.com).

6.3. Cultural Transmission

Traditional male dormitories (“morungs”) serve as cultural institutes where elders teach youth crafts, social responsibility, folklore, and agrarian wisdom (magikindia.com).

7. Challenges and Adaptive Responses

7.1. Human–Wildlife Conflict

Rising wildlife populations created crop damage from boars, porcupines, and birds. In 2019, the council introduced a controlled three-day hunting permit for farmers to protect subsistence crops—a regulated response balancing conservation and farming needs (theguardian.com).

7.2. Tourism-Driven Waste

Tourism-induced litter—wrappers, glass, plastic, alcohol containers—has emerged as a key challenge . In response, Khonoma intensified awareness campaigns and improved infrastructure like bins and monthly cleanups .

7.3. External Development Pressures

Government and commercial interests in logging, infrastructure, or hydel projects pose latent threats to the village’s forests. Khonoma’s robust governance structures help resist such incursions .

8. Broader Implications and Lessons

8.1. Community-Led Conservation

Khonoma exemplifies the power of grassroots governance. The village’s autonomy over its land, assets, and traditions enabled effective and adaptable stewardship—contrasting with top-down conservation models often constrained by bureaucratic and economic inflexibility.

8.2. Indigenous Knowledge Integration

By incorporating indigenous agricultural practices (alder-based jhum), habitat knowledge, and cultural values into conservation strategies, Khonoma demonstrates how traditional practices can have scientific validity and sustainability (morungexpress.com).

8.3. Sustainable Livelihoods

Linking conservation to income—through ecotourism, handicrafts, organic farming—creates a virtuous cycle where biodiversity enhances prosperity, and vice versa. Khonoma’s homestays, nurseries, and crafts provide scalable models for rural economies.

8.4. Adaptive Governance

Khonoma illustrates a nuanced approach to environmental policy: outright bans on destructive activities, combined with targeted flexibility (e.g., nuisance animal culling), ensures fairness and ecological health.

8.5. Replicability

With over 700 CCAs in Nagaland and Khonoma’s leadership in forming NCCAF and receiving national and global recognition, this model is replicable for communities across India and beyond (theguardian.com).

9. Conclusion

Khonoma Village stands as a testament to indigenous innovation and resilience in environmental governance. What started as a warrior outpost has transformed into a globally lauded model of sustainable harmony. With flourishing wildlife, secure food systems, eco-conscious tourism, and vibrant traditions, Khonoma narrates a compelling vision: that communities, when empowered and engaged, can craft balanced futures where conservation, culture, and economy can thrive in unison.

As we confront global environmental crises, the lessons from Khonoma—autonomous governance, cultural integration, sustainability-based economies, and adaptive policy—offer a blueprint worth emulating. Asia’s first Green Village isn’t just a symbolic achievement; it’s a working ecosystem of hope, wisdom, and dignity.