Introduction

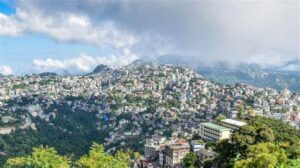

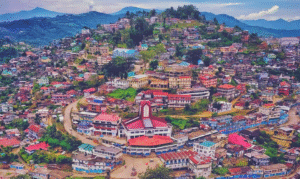

Tucked away in the rolling hills of Nagaland, Mokokchung stands as a vibrant testament to the cultural richness and traditional values of the Ao Naga tribe. Known as one of the most prominent cultural and intellectual centers in Nagaland, Mokokchung is more than just a geographical region—it is the heart of Ao identity, wisdom, and communal spirit. This town and its surrounding villages are steeped in history, ancestral knowledge, and evolving traditions that beautifully blend the past with the present. Through festivals, oral literature, age-old customs, and changing socio-political landscapes, Mokokchung continues to serve as a beacon of cultural continuity for the Ao Naga people.

This academically educational blog explores the historical background, socio-cultural dynamics, festivals, traditional institutions, language, and the emerging urban influence in Mokokchung. It aims to capture the significance of this cultural hub as a living archive of Ao Naga heritage.

1. Historical Overview of Mokokchung

Mokokchung, derived from the Ao words “Mokok” (unwillingly) and “Chung” (group or gathering), reflects a deep narrative rooted in tribal lore. The name is said to originate from an ancient Ao tale in which a group of people reluctantly left their original village to establish a new settlement. Over time, Mokokchung evolved from a tribal village cluster to a town known for education, governance, and cultural leadership.

During British colonization, Mokokchung emerged as a key administrative center. The introduction of Western education and Christianity by American Baptist missionaries significantly influenced Ao society. Mokokchung became one of the first regions in Nagaland where formal education was introduced, contributing to a wave of socio-cultural transformation among the Ao Nagas. Today, Mokokchung continues to uphold its status as an intellectual and cultural powerhouse.

2. The Ao Naga Tribe: People of Mokokchung

The Ao Nagas are among the major tribes of Nagaland, traditionally inhabiting the central parts of the state. Mokokchung is their most important district, encompassing several traditional Ao villages such as Ungma, Longkhum, Mopungchuket, and Aliba.

The Ao people trace their ancestral roots to the mythical village of Longterok (“Six Stones”), a sacred site believed to be the point of origin for the tribe. They follow a strong lineage-based social structure and have historically been engaged in agriculture, headhunting (in the pre-Christian era), and village-based governance through the Putu Menden (village council).

Today, while modernity and urbanization have influenced many aspects of Ao life, the community continues to uphold its traditional values, respect for elders, and indigenous identity.

3. Language and Oral Traditions

The Ao language, part of the Tibeto-Burman family, plays a central role in the identity of Mokokchung’s people. The dialect is divided into Chungli and Mongsen, with Chungli Ao being more widely used in formal communication, literature, and media.

Ao oral literature consists of folktales, myths, chants, and proverbs that have been passed down for generations. These oral traditions are crucial in preserving the tribe’s historical memory, moral values, and spiritual beliefs. Elders often narrate these stories to the younger generation, reinforcing cultural continuity.

Even with increasing exposure to English and Hindi due to education and migration, efforts are being made in Mokokchung to preserve the Ao language through radio programs, church services, school curricula, and published literature.

4. Traditional Festivals and Celebrations

Mokokchung is the cultural heartbeat of the Ao tribe, and this is most vividly expressed in its traditional festivals. Among the most significant is Moatsu Mong, celebrated every May after the sowing season. This festival marks a period of rest, purification, and thanksgiving. It involves feasting, singing, traditional games, and the performance of warrior dances that honor ancestral bravery and unity.

Another important festival is Tsüngremong, celebrated in August after the harvest. It is a time of rejoicing, social bonding, and expression of gratitude for agricultural abundance. Cultural performances, traditional attire, and storytelling are integral to the festivities.

Both Moatsu and Tsüngremong are celebrated with equal fervor in both rural villages and urban centers like Mokokchung town, indicating the unbroken thread between tradition and contemporary life.

5. Social and Cultural Institutions

Mokokchung is home to several institutions that serve as custodians of Ao culture and community organization. One such institution is the Putu Menden or the traditional village council, which continues to play a vital role in resolving disputes, organizing festivals, and managing community affairs.

Churches also hold a central place in Ao society, especially since the mass conversion to Christianity in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The churches in Mokokchung are not just places of worship but also hubs for education, literature, and social service. The Ao Baptist Arogo Mungdang (ABAM), headquartered in Impur near Mokokchung, is a major religious and cultural body that guides spiritual and ethical life among the Aos.

Another important cultural body is the Ao Senden, a tribal apex organization that works for the socio-political rights of the Ao people. These institutions symbolize the blend of traditional governance and modern civil society.

6. Role of Women in Ao Society

Women in Mokokchung play an essential yet often understated role in preserving and transmitting Ao culture. Traditionally, women were responsible for managing households, participating in agricultural work, and practicing indigenous crafts such as weaving.

Ao women are particularly skilled in handloom weaving, producing intricate patterns and traditional motifs that are unique to each clan or village. The mekhela and shawi—Ao traditional shawls and skirts—are often woven by women and worn during cultural events and ceremonies.

In contemporary Mokokchung, women are also active in education, administration, and the church. While societal norms continue to evolve, the empowerment of Ao women through education and entrepreneurship is increasingly visible in the town and its neighboring areas.

7. Traditional Architecture and Village Planning

The traditional Ao Naga village architecture is both symbolic and practical. Villages such as Ungma and Mopungchuket near Mokokchung still retain elements of indigenous design—wooden houses with central hearths, carved posts, and log drums (kongkhim) used for village communication and celebrations.

The morung or bachelor’s dormitory, though largely ceremonial today, once served as a vital educational and social institution where young boys learned tribal lore, warfare skills, and ethical values under the guidance of elders.

Village planning in Mokokchung district typically revolves around a central space for festivals, log drums, and community gatherings, reflecting the communal nature of Ao society.

8. Education, Literature, and Cultural Evolution

Mokokchung has earned the title “the intellectual and cultural capital of Nagaland” due to its educational heritage. Schools like Mayangnokcha Government Higher Secondary School, Fazl Ali College, and many mission-founded institutions have contributed to high literacy rates and cultural consciousness in the region.

Ao authors, poets, and scholars have contributed significantly to Nagaland’s literature, writing in both Ao and English. Journals, church newsletters, and academic publications often originate from Mokokchung, keeping the flame of knowledge and cultural reflection alive.

The town also hosts cultural events, seminars, and literary meets that serve as forums for discussing tribal identity, inter-tribal relations, and the challenges of modernity.

9. Urbanization and Modern Influence

As one of the oldest urban centers in Nagaland, Mokokchung balances modern infrastructure with tribal traditions. The town features government offices, hospitals, restaurants, and digital amenities, but retains its identity as a close-knit community with shared cultural roots.

Urbanization has brought challenges such as migration, intergenerational gaps, and a shift from agrarian livelihoods to service-based employment. However, Mokokchung remains resilient in its cultural values, thanks to community-driven efforts to retain language, arts, and festivals.

10. Tourism and Cultural Preservation

Tourism in Mokokchung is slowly growing, with travelers drawn to its scenic villages, cultural museums, and heritage festivals. Places like Longkhum village are known for their panoramic views and folklore, while Mopungchuket has become a model village showcasing cleanliness and traditional culture.

The district also houses the Ao Museum, which preserves artifacts, tools, and traditional costumes. Guided village walks, heritage homestays, and participation in festivals like Moatsu offer visitors an immersive experience into Ao life.

Efforts by community elders, local NGOs, and state bodies continue to focus on sustainable tourism, ensuring that cultural tourism benefits the local people while safeguarding traditional practices.

Conclusion

Mokokchung is not just a town—it is a living narrative of the Ao Naga tribe’s journey through history, culture, and modernity. From ancient oral traditions to contemporary literature, from warrior dances to Sunday choirs, and from log drums to smartphones, Mokokchung embodies a unique cultural duality. It stands as a microcosm where identity, tradition, and change coexist harmoniously.

By valuing its indigenous roots and embracing educational and social evolution, Mokokchung continues to be a cultural hub and a beacon of Naga heritage. For researchers, anthropologists, students, and travelers alike, Mokokchung offers invaluable insights into the resilience, richness, and relevance of tribal culture in the 21st century.